Multi-cloud strategy can seem appealing at first. But as firms scale, they’re hit with overwhelming issues that can break more than the bank

Sovereign cloud has moved from buzzword to board-level concern. The EU is tightening its Cloud Sovereignty Framework, the Data Act is coming into force, and initiatives like Gaia-X, national “cloud de confiance” programmes and sector data spaces are maturing.

At the same time, hyperscalers are launching their own sovereign offers: AWS European Sovereign Cloud operated only by EU entities, Google’s extended “sovereign cloud” options in partnership with players like Thales, and similar moves from others.

In that context, many organisations ask a deceptively simple question:

“Should we go for a fully sovereign cloud, or should we optimise for best of breed and not care where the data sits?”

As CTO, CIO or CDO, I would never answer this with a binary yes/no. It is the wrong question. Sovereign cloud is not a product to tick on a procurement list. It is a strategy that must be designed, case by case, for a given industry, a given company and a given portfolio of data and workloads.

This article explains why there is no universal answer, why “just use two clouds” is usually not the solution, and how I would structure a real decision process at C-level.

A lot of confusion comes from mixing three different ideas:

Any sovereign strategy that does not clearly separate these three dimensions will lead to bad decisions.

The “obvious” answer some teams jump to is:

“We will put sensitive data on a local sovereign cloud and keep everything else on a global hyperscaler. Best of both worlds.”

On paper, that sounds reasonable. In practice, a real multi-cloud strategy is one of the hardest things to execute at scale:

This does not mean multi-cloud is always wrong. It means it must be a deliberate design decision with clear scope and guardrails, not a reflex.

Saying “it depends” is not enough. The role of CTO, CIO or CDO is to turn that into a structured strategy that a board can understand and own.

For a sovereign cloud decision, I would always work along at least four axes:

The output is not “yes sovereign / no sovereign”. It is a map of where sovereignty is non-negotiable, where it is desirable, and where global best of breed remains the rational choice.

Examples include:

Everything else can remain on standard global regions.

Key condition: treat this as one enterprise platform with unified identity, governance and security. and accept all tradeoffs and remember them in futur discussions.

Here, a hyperscaler is the primary platform, but you apply strong sovereignty controls:

In some industries, the real question is not “which cloud provider” but “which ecosystem” you must join.

Examples include sector data spaces like Catena-X or healthcare data spaces aligned with EU programmes.

In those cases, sovereignty is about federation, standards and data-sharing rules.

A central question remains: when international cloud providers claim they will operate sovereign environments fully independent from their native market, how realistic is that promise?

The operational separation can be feasible: EU-only staff, isolated regions, contractual and legal firewalls. But the real friction lies in the code itself.

Global cloud platforms are built on globally shared codebases, engineering pipelines and service architectures. Rewriting all cloud services natively for each sovereign market would require:

In practice, most hyperscalers centralise their builders, and sovereign variants still rely on large parts of the global codebase. This is not necessarily a problem, but it is a reality that executives must understand when assessing technical and legal sovereignty claims.

This concern reinforces why sovereignty is never a binary choice and why a realistic strategy must look beyond marketing labels.

If a board asks:

“Are we going sovereign or not?”

my honest answer is:

“We will define where we must be sovereign, where we should be, and where it is not worth the trade-off.”

There are several reasons.

Going strict on sovereignty can mean:

Optimizing for global innovation can mean:

Multiple clouds can become unmanageable without:

Clarify business priorities, regulatory landscape, and strategic constraints.

For each domain, assess sensitivity, regulatory obligations, performance and interoperability needs. It has to be done, end-to-end (tedious task should I remind?)

Assign the three patterns to different data and workload categories.

Compare candidate architectures on cost, compliance, innovation, dependency risk and long-term viability.

A sovereign cloud strategy only works if leadership and teams understand the trade-offs and practices.

The industry often uses the term “sovereign cloud” without defining what sovereignty really includes. In reality, true cloud sovereignty spans several layers, and each layer raises difficult questions that go far beyond data location.

Data residency is the simplest dimension: storage, processing and backups kept within a specific geography. But residency alone does not guarantee sovereignty.

Operational sovereignty requires that the people administering, supporting and securing the cloud are subject only to the laws of the intended jurisdiction. This raises questions:

Even if data is local and staff are local, a provider headquartered elsewhere may still be subject to foreign laws, potentially enabling extraterritorial access requests. This is where the risk lies with global hyperscalers.

Even the best-isolated region still depends on a global codebase maintained by engineering teams outside the jurisdiction. Key questions remain:

In most cases, the answer is no—cloud services are too deeply integrated globally.

Cloud is not just a data repository, it's based on very important services that make applications, products and most of the internet.

Another dimension seldom discussed openly: could a sovereign or semi-sovereign cloud be unplugged for political reasons?

True sovereignty requires thinking through the resilience of the entire ecosystem.

Cloud sovereignty is not about one factor but a multi-dimensional posture combining:

This is why cloud sovereignty is inherently complex and why simplistic yes/no positions are inadequate.

European organisations must take sovereignty seriously. But choosing a provider without deep analysis is dangerous.

The real work is:

More details about my approach are available at: www.douchinconsulting.com.

#CloudSovereignty #SovereignCloud #CloudStrategy #DigitalSovereignty #DataGovernance #CloudSecurity #CIO #CDO #CTO #EUDataAct #GaiaX #MultiCloud #HybridCloud #CloudTransformation #EnterpriseCloud #TechLeadership

Expert analysis on data, cloud, and change management.

Europe can't afford to play catch-up. While others race to 3nm, we should leap directly to 2nm, just like Japan is doing with Rapidus. It’s bold, risky, and exactly what we need. In this article, I argue why Europe should go all-in on 2nm and what it would take to make it happen.

Are you a Prompt Engineer? Discover what it is really about.

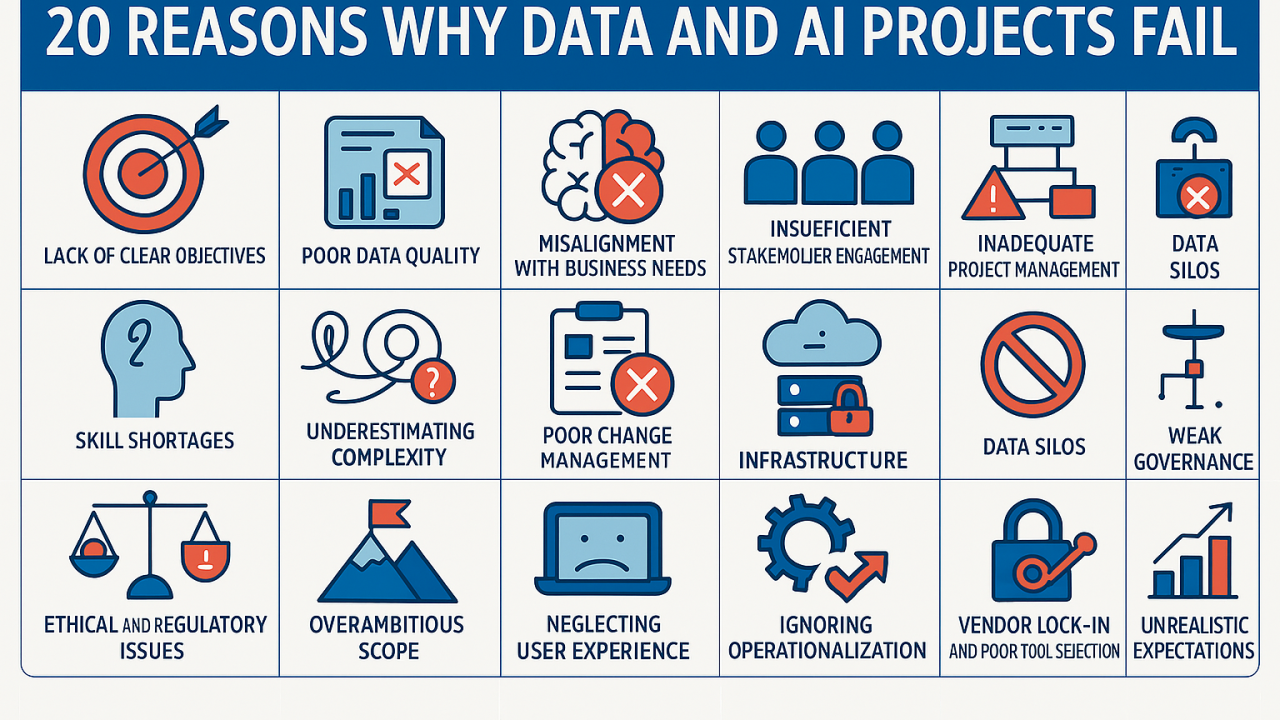

Avoid AI an Data failure, learn from other company's mistakes

Expert guidance for seamless cloud and data transitions. Unlock value, ensure compliance, and lead with confidence.